We want to reduce the number of victims of dangerous driving, including drunk driving, to zero.

To achieve this, it is essential to utilize technology. Especially in recent years, with the advancement of the Internet and digital technology, safe driving and operation management, such as alcohol checks and roll call systems, are rapidly becoming digitalized and ICT-based.

We at Tokai Electronics are a company that specializes in accident prevention technology, particularly in the area of drunk driving prevention technology.

Before the invention of the breathalyzer, police officers had to rely on their own judgment based on smell, complexion, gait, and behavior.

In the United States, where regulations on drunk driving began to be put in place along with the development of automobiles, initially, drinking status was measured using blood and urine samples.

In 1927, Dr. Emil Borgen conducted an experiment in which he placed sulfuric acid and potassium dichromate in a soccer-ball-sized air bag (a.k.a. a balloon) and examined the correlation between the effects on blood and breath.

When the breath was blown into a breath bag, the color of the breath changed depending on the alcohol content, allowing the concentration to be determined. However, in this state, it was still not ready for practical use on the roads.

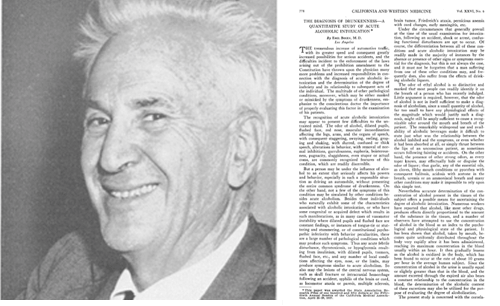

“THE DIAGNOSIS OF DRUNKENNESS A QUANTITATIVE STUDY OF ACUTE ALCOHOLICINTOXICATION”

This report, published by Dr. Borgen in 1927, gives us a glimpse into the state of the automobile society, drunk driving regulations, and alcohol testing technology of the time. This paper led to the recognition that breath alcohol concentration is an equivalent indicator of blood alcohol concentration.

This is considered to be the beginning of the history of "breath alcohol concentration measurement."

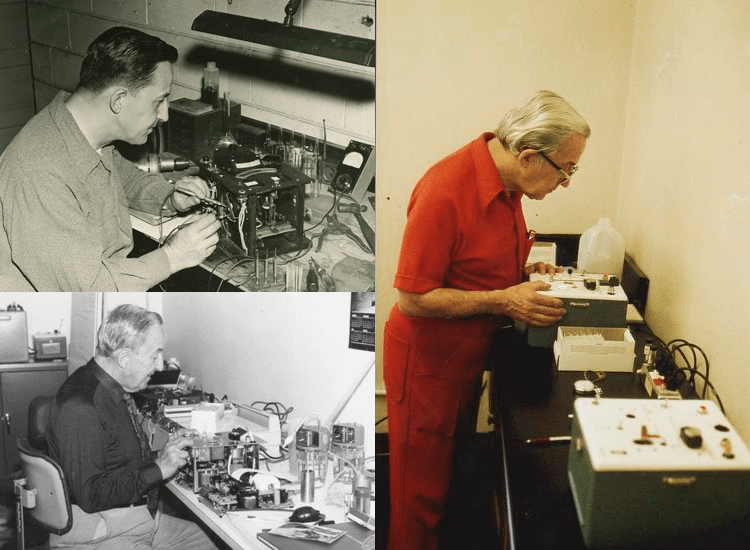

Following Dr. Borgen, police in every state began researching alcohol detection technology. In 1936, Dr. Harger, a biochemist at Indiana University, developed and patented a device called the "Drunk-O-Meter."

Using a balloon into which the person blew, it was the first practical breathalyzer to measure a person's intoxication.

It is considered the first generation of breathalyzer.

Dr. Hargar also contributed to drafting a model bill that legalized the use of chemical test evidence of intoxication and set limits on alcohol concentration for drivers.

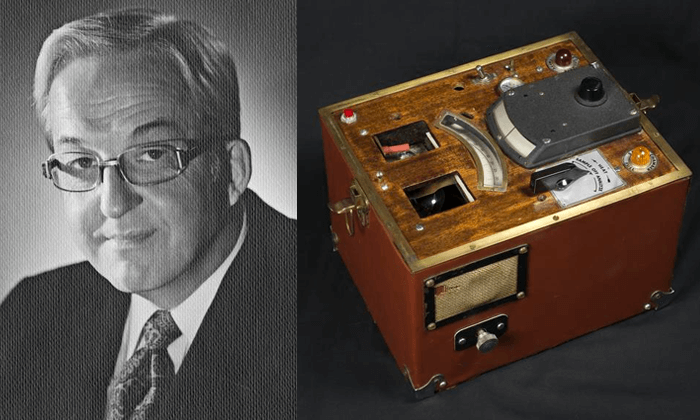

Professor Borkenstein improved on Dr. Harger's Drunk-O-Meter and invented the first practical breathalyzer. While the Drunk-O-Meter looked like something out of a chemistry lab and needed recalibration each time the device was moved, Professor Borkenstein's device was very portable. This was followed by more compact breathalyzers that looked less like those typically found in scientific laboratories, leading to the widespread use of roadside breathalyzers in the early 1960.

Professor Borkenstein's breathalyzer was trademarked as "Breathalyzer" and became widely available. Electronic analysis began to be used for breathalyzers, marking the beginning of the second generation of breathalyzers and the beginning of the history of breathalyzers.

The breathalyzers created by Borkenstein subsequently evolved into the Models 900, 900A, 900B, and the microprocessor-controlled, infrared absorption model 2000.

Over 30,000 Borkenstein breathalyzers of various models were manufactured and sold between 1955 and 1999. In use for many years in the United States, Canada, and Australia, they continued to be the standard breathalyzer used by law enforcement agencies.

In 1974, the US NHTSA subsequently developed and published a breathalyzer certification system and a list of approved products.

Since Borkenstein's breathalyzer, successors have evolved this device and technology. Today, the number of situations in which it is used has increased, from personal use to business use to professional drivers. In addition, various sensing and analysis technologies have been developed according to the purpose, such as infrared analysis, fuel cell (electrochemical) sensors, and semiconductor gas sensors.

With the advancement of breath alcohol technology, from the late 1970s onwards they also began to be used as alcohol interlock devices.

Advances in breath alcohol detection technology have a history of greatly contributing to traffic society by providing an objective indicator that can eliminate previously overlooked cases of drunk driving and illegal oversight by police officers. Numerous scientists, biochemists, and researchers have contributed to this history.

Not only did Dr. Harger and Dr. Borkenstein establish breath alcohol analysis technology, but they also made significant contributions to the legal status of breath alcohol concentration, such as lobbying governments to strengthen drunk driving regulations.

Notably, Dr. Borkenstein is also the founder of the Borkenstein Award, an academic research award currently offered by the International Association Chemical Testing (IACT).

In this way, the contributions of biochemistry researchers and the development of alcohol detection technology have grown over time, and now drunk driving prevention activities have become a field that can almost be called an "industry," with industries such as the breathalyzer and alcohol interlock, continuing to contribute to zero traffic fatalities.

Borkenstein Award

Recognizing an individual who has made outstanding contributions through a lifetime of service in the field of alcohol/drugs as they relate to traffic and transportation safety in keeping with the ideals and work of Dr. Robert F. Borkenstein.

https://www.iactonline.org/page-1699019

Typically, alcohol that enters the body is absorbed into the bloodstream within about 30 minutes. Ideally, blood samples would be required for measurement. However, there is a law for indirectly converting concentrations, allowing us to measure alcohol concentration from breath samples without sampling blood. This law is called Henry's Law.

Henry's Law

Henry's Law is a general law of physical chemistry. Simply put, it is a fundamental theory that states that when a substance dissolved in a liquid is present in air (vapor), there is a constant direct proportionality, and when a substance in air (vapor) is dissolved in a liquid, there is a constant direct proportionality. It predicts that when a volatile substance such as alcohol is dissolved in a solvent (such as blood), the concentration of alcohol in the gas (i.e., breath) will be proportional to the concentration of alcohol in the body.

Since the early days of breath testing, Henry's Law has traditionally been used to convert blood and breath concentrations using the following concentration conversion formula:

"The weight of alcohol in 1 liter of blood divided by 2100 is equal to the weight of alcohol in 1 liter of breath."

Currently, most breathalyzers that measure alcohol concentration based on breath testing use this law. Our company also uses this law for conversions. However, this law is only an approximation, not an absolute value. In reality, measurement values vary due to factors such as pulmonary ventilation and cardiac pulse. Furthermore, variations due to external factors such as sensor sensitivity and the operating environment must usually be taken into account.

Currently, sensing methods can be broadly classified into four types: semiconductor method, fuel cell method, non-diffuse infrared absorption method (NDIR), and chemical reaction method.

We will introduce specific breath alcohol concentration sensing technology.

| Sensor method | Semiconductor method | Fuel cell method | Non-diffused infrared suction method(NDIR) | Chemical reaction method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas selection type |

△ |

◎ |

〇 |

△ |

| Accuracy |

△ Aging |

◎ |

〇 Humidity, temperature, pressure |

△ |

| Lifespan |

〇 |

△ 2 to 5 years |

◎ |

× disposable |

| Responsiveness |

◎ About 5 seconds |

△ Long burning time |

〇 |

× |

| Price |

◎ |

△ Expensive/consumables |

× Precision optical equipment |

× Running cost |